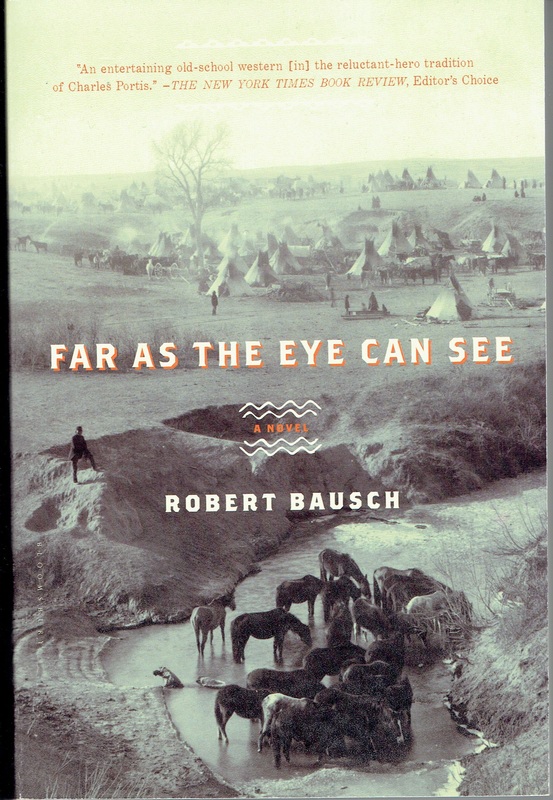

During the last twelve months or so I have been on a roll as far as American fiction is concerned with a number of excellent novels read: Philip Meyer’s The Son, Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried, Laird Hunt’s Neverhome and Kent Haruf’s Our Souls at Night all rack up maximum star ratings. To that list we can now add Robert Bausch’s Far as the Eye Can See which sits easily amongst these highly rated novels.

I am indebted to those good people at Round Lake bookstore in Charlevoix, Michigan for bringing this book to my attention (pop in if ever you are passing as it is a lovely independent book shop) and enhancing my holiday reading during my visit to the States.

As a deserter from the American Civil War, Bobby Hale is not the most admirable of narrators as he admits to re-enlisting several times under assumed names in order to pick up the related financial bonus. Without ever distinguishing himself in warfare he later joins a wagon train heading west where one of his first acts is to kill an Indian in an unnecessary attack. This, in the blunt words of the wagon train leader, is murder and the act sets the course for the remainder of the novel as Bobby Hale embarks upon a journey in a vast landscape where bloodshed and death feature regularly. Nor is this allayed by love. Hale is at one stage married to an Indian woman and whilst he begins to appreciate the comforts this brings, when she leaves him for another Indian he remains largely unaffected. He is later betrothed to Eveline, a woman travelling with the wagon train but he is unable to keep his promise to return to her before setting off west. That Hale retains our sympathy is down to his skilful depiction by Bausch and the authenticity of the first-person narration.

As with any picaresque novel, the protagonist grows in self-knowledge and when Hale begins to show concern for the welfare of others, particularly Ink a young girl who is running away from an Indian marriage and Little Fox, an orphaned Indian boy, he realises that man is always faced with a choice for his actions. As he begins to accept this wider responsibility, the novel moves towards an utterly gripping, heart-stopping conclusion.

Of course there are wider issues to consider beyond personal morality, issues such as the role of women, white man’s treatment of Indians and the establishment of law and order. And as the novel takes in the Battle of Little Big Horn and its subsequent events, it is difficult to ignore the metaphorical nature of the book. But whether you read this book as a personal adventure or a “birth of a nation” novel you should find yourself entirely engaged. It comes highly, highly recommended.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed