Mark Connors

Throughout literature there are numerous protagonists who don’t fit in, characters who at best march to a different drumbeat or at worst are castigated as mad. Salinger’s Holden Caulfield in The Catcher in the Rye and Christopher John Francis Boone in Mark Haddon’s, The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night Time spring immediately to mind, characters who, despite not fitting in, point up the absurdities of society or the burden of being normal.

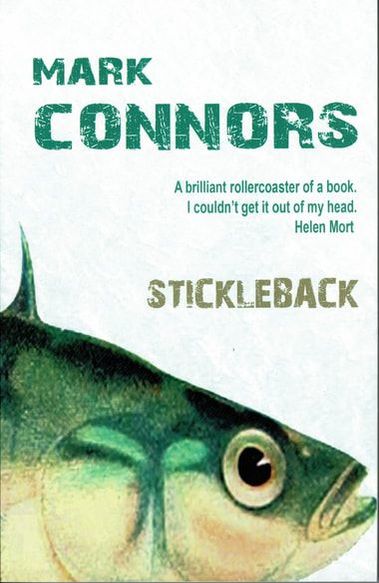

To that list of characters, we can now add Alan Siddall in Mark Conner’s, Stickleback, a character who might prove to be the most unlikely anti-hero of all. Siddall is a 68-year-old Black Sabbath fan who alerts our sympathies as the resident of a Mental Health Unit facing a transfer to another facility at the behest of the health bureaucracy. Siddall leads a life of apparent aimlessness involving a succession of cigarettes, cups of tea and wanderings around Leeds which often end in the police returning him to his unit. But gradually, it is revealed that Siddall has a bi-polar condition and a history of attempted suicide. But make no bones about it, as a foul-mouthed, utterly selfish individual with a penchant for masturbating in public, he strains readers’ sympathies to the full.

As the novel develops, our “hero” descends into a spiral of hopelessness as more and more drugs are prescribed and administered not so much as to “cure” him but to control him, to keep him manageable. Docility is prized above long-term recovery but the nightmares which these drugs induce become increasingly vivid and disturbing.

The longing for some kind of uplift or release becomes most intense and a tormented climax is reached via a masterful piece of repetition by Connors. It arrives via a brilliant analogy from the author, an analogy which incidentally, also answers questions around the choice of title for this book, but more importantly, there is a clear suggestion of how people such as Alan Siddall can be treated with compassion, dignity and respect.

Stickleback carries a painful lesson. We might laugh at Siddall’s, often profane and scatological, turn of phrase but it is a difficult read. It is also a piece of bravura writing, a sustained first-person narrative which reeks authenticity and passion. On finishing I felt as though I had been through the proverbial wringer, but as with reading all powerful novels, I also felt as though my perception of the world had undergone a significant shift. I highly recommend this book.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed