Ours wasn’t a house which was geared to take on board the full impact of the rock and roll revolution. As far as playing music was concerned, we had a gramophone, a stately piece of furniture which sat in the room we called the parlour and would later become the sitting room. I don’t recall the radio function of the gramophone ever being used as it had been superseded by a transistor placed in the kitchen, and the record playing facility was only occasionally employed to give long playing recordings of South Pacific and the Sound of Music an airing. There was a collection of 78s; discs which had the solidity of dinner plates and which dropped from the spindle to the turntable with the sound of a tree being felled. There were no rock and roll gems amidst this collection unless you count Eddie Calvert and his Golden Trumpet or Bing Crosby crooning about a white Christmas. So, musically, the Beatles were, in George Harrison’s words, about to save Britain from boredom, but as far as our house was concerned the ruling passion was still ennui and musical tastes were governed by Sing Something Simple played over the kitchen transistor on a Sunday evening.

In fact, in our northern outpost city, the whole sixties revolution seemed to pass us by. It was like a giant party taking place in next door’s house and we could only witness it by wiping away condensation and then peering through the window. Philip Larkin famously said that sexual intercourse didn’t exist until the Beatles first LP. From a personal point of view, my thanks are extended to Rod Stewart’s Every Picture Tells a Story in 1971. Shit! I can see you counting on your fingers, doing your sums and looking doubtful. Okay, what about Dylan’s Blood on the Tracks in 1974?

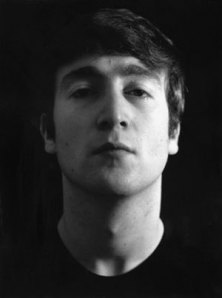

Not that the Beatles could be ignored of course. News of the Fab Four phenomenon (try saying that when you’re pissed) was brought to us by the Daily Mirror. The Beatle hits were included in the Junior Choice play list on a Saturday morning sitting snugly alongside the Laughing Policeman and the Ugly Duckling , and we were allowed to stay up late to watch them on the Royal Variety Performance. Or rather we weren’t allowed to watch because as the evening wore on, it was deemed to be too late and we were duly packed off to bed. Our daily newspaper didn’t let us down though, the inestimable red-topped organ (another image with which to play) told of the Beatles’ performance the next day and particular mention was made of the quip about rattling your jewellery in the posh seats; John Lennon’s quip.

And then they changed, the Beatles I mean. Their hair grew even longer, they stopped writing songs about wanting to hold girls’ hands and they made films which were surrealistic to the point of being incomprehensible. The Daily Mirror could no longer portray them as cheeky chappies from next door: their involvement in the drug culture, their anti-establishment comments, their weirdness meant that they were now exploited by the press for their shock value. And I didn’t get them any more. To my regret, Hymns Ancient and Modern retained a stronger influence than Sergeant Pepper.

I stayed with John though, retaining an affinity with the rebellious vocalist on Twist and Shout. I didn’t like his new wife or his publicity-seeking-staying-in-bed-for-a-week-antics, but there did seem to be a vulnerable figure there somewhere, still shouting for help.

We need to fast forward to December 1980. In an entirely predictable career move, (working class grammar school boy demonstrates vocational need to “put something back”) I had completed a Post Graduate Certificate in Education and I had taken up a post to teach English in a boys’ school in the south of England. The training had been ineffectual at best, although a drama lecturer who insisted on a practical rather than a theoretical approach was an honourable exception, and most of our lectures and seminars took place in the pedagogical safety of an ivory tower unencumbered by pragmatic experience of the real world of education. This was years before computers would be commonplace in schools, interactive whiteboards were a fantasy of Dan Dare proportions and although VHS was beginning to poke its nose through the door, it was still engaged in a life or death struggle with Betamax. No, in order for technology to provide a variety of experience in the classroom, the teacher would have to march in carrying a record player. We did have a tutorial where such an approach was suggested and this in itself was sufficient to convince me that I would never teach a lesson where I encouraged pupils to look at the interesting word play in She’s Leaving Home (“What did she hope the note would say?”) or the ambiguities in The Sound of Silence (How can silence have a sound?”) This was five years after Anarchy in the U.K. for God’s sake.

But on the morning of 9th December 1980, I altered my lesson plans. In the time honoured tradition of giving the fresh-faced probationary teacher the sink groups I taught the bottom set in the third year. I also taught some of these boys for “Extra English”, a timetabling brainwave to deal with the fact that they didn’t study a second foreign language, and some of these lads turned up a third time because they didn’t study French. The most benighted of the boys suffered me for seven lessons a week others had me for five lessons whilst the lucky minority had only three lessons but the overall effect was mutual fear and loathing in the cause of English; the civilising subject. Most of my lessons were a disaster and I could see my worthily chosen new career disappearing down the exit marked pan.

Kenneth, Kevin and Devon weren’t interested in simple, compound and complex sentences; they were more interested in “reccing.”

“Wrecking?”

“Yes sir, reccing.” The activities they got up to at night on the recreation ground, the Rec. Cheung was more interested in how loud he could fart in class and it was left to Simon to show that some of the pupils were amenable and would make their best effort. It was Simon I asked to read James Reeves’ poem, Slowly aloud to the class.

Slowly

Slowly the tide creeps up the sand,

Slowly the shadows cross the land,

Slowly the cart-horse pulls his mile,

Slowly the old man mounts the stile.

Slowly the hand moves round the clock,

Slowly the dew dries on the dock.

Slow is the snail – but slowest of all

The green moss spreads on the old brick wall.

And gamely he set off to read in the face of mounting derision as I suddenly remembered that Simon was the boy in the class with a pronounced lisp.

I was once confronted by the considerable arms folded presence of Kenneth’s mum at Parents’ Evening. Mustering all of my new professionalism I mentally blanked out images of the housemaid with the sweeping brush in the Tom and Jerry cartoons.

“Kenneth needs to work on aspects of grammar,” I told her, “verb endings and the use of the definite article.” She listened politely until I, suddenly aware of my own monumental pomposity, stopped speaking. There was a moment’s further pause before Kenneth’s mum spoke,

“If dat boy give you any trouble, you hit dat boy.”

Corporal punishment had not yet finished its miserable life-cycle in English schools but the thought of adding to the general mayhem of most of these classes with the added excitement of physical beatings was not one I was prepared to entertain. Progress, if it was to be made, lay in a different direction.

It wasn’t until it dawned on me that I wasn’t actually expected to teach these lads anything but simply keep them quiet that the breakthrough occurred. There was no point in banging on about sentence construction until there was a desire or a need to actually construct a sentence. That’s when we started to discuss Caribbean backgrounds and Sikh traditions, that’s when we had a weekly kickabout with a football in what was a traditional rugby and hockey playing school. And that’s when I felt confident enough to change my lesson plans on the morning of December 9th, 1980.

On that morning I did march into the classroom with a record player and I played some Beatles music and we talked about how, on the previous evening on a New York street the writer of All You Need is Love, Give Peace a Chance and Imagine had been murdered. And after that lesson and the ones that followed, the boys in that class knew that their English teacher had had a life before teaching, and in fact, he had once been a teenager himself when he’d allayed some of the doubts and insecurities of those years by using a by turns witty and caustic, cruel and sympathetic, Liverpudlian as a touchstone in an increasingly perplexing world.

Why, thirty years on, this meditation on the influence of John Lennon? Simply because art can do that, art can jerk you out of the ordinariness of life and catapult you back to significant times, times when the world looked a lot different. It can also cast a light up to the present time, a mirror held up to nature and all that.

Thirty years on the fire in this English teacher’s belly has been well and truly dampened. A tribute this to the whole edifice of educational progress: the national curriculum, the countless government strategies, league tables, target-setting, the relentless push for accountability and the reduction of English into a single, measurable entity; the whole stultifying bundle. And ultimately, the flames of passion died in the face of mental illness.

I moved to Yorkshire in 1990; twenty miles south east of Bradford. My brother in law lived a similar distance to the north west of Bradford and he suggested meeting up for a curry at the Kashmir restaurant and a film at what was then the National Museum of Film, Television and Photography. I forget the first film we saw, it was possibly The Mission, but the outing must have been a success as it became a regular fixture, so much so that it is now a monthly event, and one of our most easily kept New Year’s resolutions is to watch at least twelve films during the course of the year at what is now snappily re-branded as the National Media Museum.

January saw us get off to a cracking start with Sam Taylor-Wood’s Nowhere Boy, featuring the early life of John Lennon and the formation of a group which would eventually become the Beatles. Owing to our idiosyncratic planning methods, not all of our film choices can be described as good. Some of them fall a long way short of good and we plod our weary way home with only the consolation of a top notch curry as consolation. The evening of Nowhere Boy though was one of those evenings when all of the elements fall together into a very satisfactory whole.

The film opens with the highly recognisable chord from the beginning of A Hard Day’s Night and holds the attention from thereon. Aaron Johnson captures the cheek and the rebelliousness of the young Lennon as well as his cruelty, vulnerability and latent musical genius. Equally compelling are the performances of Kristin Scott Thomas as the tightly buttoned Aunt Mimi and Ann Marie Duff as Julia, Lennon’s real mother. The former excellently presents the frigid woman bound by duty finding difficulty in responding with any warmth to her wayward charge, whereas frigid would be the last adjective to apply to Duff’s performance. Watching the oedipal relationship between John and his mother is often a queasy task as she smothers him in kisses, dances lasciviously in a coffee bar and informs him candidly that rock and roll really means sex. But the audience’s unease at these scenes will only replicate similar feelings from earlier in the film where John and his Uncle George are seen lying on a bed and sharing the contents of a hip flask. “He was more than an uncle to me,” says the young John after the death of Uncle George and we are left to ponder the full implications of this cry.

The tragic death of Julia follows that of George and we see Lennon caught in a Freudian nightmare. No wonder music offers a way out.

And it was music which played in my head as I made my way out and drove gingerly on the ice-bound M62. Two things bothered me on the way home apart from the treacherous conditions. Firstly, there was the song, Woman. Not one used in the film but one of the songs I had played in those lessons in the classroom. As part of the Double Fantasy album it reached the top of the charts in the U.K undeniably assisted by an outpouring of grief by the record buying public. But as an expression of love which is “written in the stars” it is flabby; floundering around in confessions of thoughtlessness and regret for causing sorrow or pain, and whilst Lennon’s references to the “little child inside the man” are particularly pertinent in relation to Nowhere Boy, retrospectively, the song does not really stand comparison with McCartney’s, Maybe I’m Amazed released by the oft-derided Wings. Here, being left inarticulate when faced with trying to express the extent of love reaches a paradoxical zenith: fast, powerful and compulsive, the song, for me, is redolent of a seventies student bed-sit and a love affair which despite its pitiful outcome left me amazed.

What profit is there after all in measuring the Beatles against the Stones, or indeed Lennon against McCartney? But as the signs for the M621, Beeston and Leeds slipped slowly by in the dark I couldn’t help realising that here, in comparing these two songs, my favourite Beatle came off second best.

And the second things which concerned me, returning as a flickering image in the memory, was the thought of whatever became of those boys in the classroom of the upstairs corridor of Hitchin Boys’ School: Kenneth, Kevin and Devon, nowhere boys who would now be in their mid-forties?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed